3D Object Detection: Why It’s Hard and What Matters in Production

Table of Contents

- TL;DR

- What Is 3D Object Detection?

- 3D Object Detection vs 3D Object Recognition in Computer Vision

- 3D vs 2D Detection: When 2D Fails and What 3D Solves

- How 3D Object Detection Works: Sensors and Data

- 3D Object Detection for Autonomous Driving

- 3D Object Detection in Robotics, AR, and Industrial Systems

- 3D Object Tracking: Extending Detection Across Time

- Training Data Challenges in 3D Object Detection

- About Label Your Data

-

FAQ

- How much 3D data is needed to reach production-level performance?

- How should 3D object detection be evaluated beyond mAP?

- When does sensor fusion outperform LiDAR-only or vision-only setups?

- How do annotation guidelines impact tracking and prediction quality?

- What are the most common failure modes when deploying 3D detection to new environments?

TL;DR

- 3D systems output geometry (position, size, orientation), which enables motion prediction and path planning that 2D can’t support.

- In production, bad 3D annotations kill performance: inconsistent box placement, unclear occlusion handling, and orientation drift across frames.

- Use 3D object detection when distance, pose, or spatial relationships determine system actions (not for pure recognition tasks).

What Is 3D Object Detection?

If you’ve worked with 2D object detection, you already know the drill. The model outputs bounding boxes in pixel space. For many use cases, that’s enough.

3D object detection changes the question from what’s in the image? to where is this object in the real world?

Instead of “there’s a car in the frame,” you get “there’s a car 15 meters ahead, angled left, moving toward us.” The output includes position (x, y, z), orientation, and physical dimensions. Geometry that enables path planning and collision avoidance, not just recognition.

Once depth matters, small uncertainties compound. A few pixels of 2D error might be harmless. In 3D, the same uncertainty becomes a bad distance estimate that affects braking decisions.

That’s why 3D bounding box object detection shows up in systems that act on what they see: autonomous vehicles, robots, drones.

Everything needs to line up in physical space, which is why we’ve seen data annotation consistency determine whether models reach production across the LiDAR and point cloud projects we handle at Label Your Data.

3D Object Detection vs 3D Object Recognition in Computer Vision

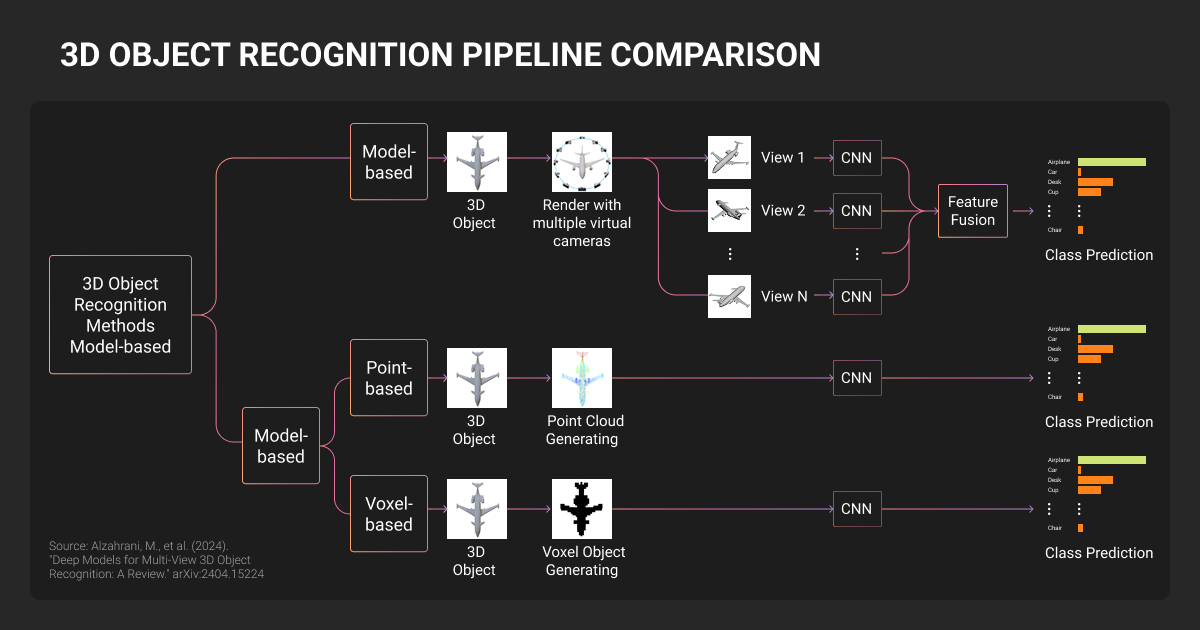

In 3D perception systems, detection and recognition answer different questions. Detection tells you where and what; recognition tells you how.

3D object detection outputs existence and geometry: there is a pedestrian at X, Y, Z coordinates, with this size and orientation. That’s enough to know where the object is in space and whether it might be in the way.

3D object recognition adds context: what kind of object this is and how it’s configured or behaving. Is that pedestrian facing left or right? Carrying a backpack? Arm extended, suggesting they might step into the road?

Detection anchors the system in physical space. Recognition adds behavioral context. Two objects at the same distance can pose very different risks once posture, orientation, or object type come into play.

Why perception systems use both

Most production pipelines use detection and recognition together, even if they’re not always labeled that way.

Here’s a simple autonomous driving example. The system detects a vehicle ahead and estimates its position and size. Recognition refines it: not just a vehicle, but a delivery truck. That matters because delivery trucks stop often, pull over suddenly, and block lanes.

Nothing about the geometry changed, but the expected behavior did. Detection kept the system grounded in space. Recognition shaped how it reasoned about what might happen next.

3D vs 2D Detection: When 2D Fails and What 3D Solves

2D image recognition tells you what’s visible. 3D detection tells you what’s happening in space.

In 2D, you detect two cars in the same frame. In 3D, the system knows one is slowing down, the other approaching faster, and their paths will intersect. That’s the difference between recognition and spatial reasoning.

Depth enables this: once you know distance, orientation, and relative position, you can reason about collision risk, object occlusion, and scene dynamics.

What you’re signing up for:

- LiDAR and depth sensors add significant hardware cost

- 3D bounding box annotation takes 5-10× longer than 2D

- Orientation and occlusion increase labeling ambiguity

- Training and inference demand more compute and memory

- Real-time latency constraints become harder to meet

When you actually need it: use 3D when spatial relationships drive decisions: autonomous driving (distance affects safety margins), robotics (grasping requires geometry), AR (virtual objects must anchor in real space).

If 2D fails on an ambiguous scale or distance, 3D is the only solution.

How 3D Object Detection Works: Sensors and Data

Input data types

Most 3D detection systems start with raw sensor data that captures geometry differently:

- Point clouds (from LiDAR) represent the world as 3D coordinates where laser pulses hit surfaces. Explicit about distance and shape. Common in autonomous driving and robotics.

- Depth maps (from stereo cameras or RGB-D sensors) encode distance per pixel. Balance geometric cues with visual context.

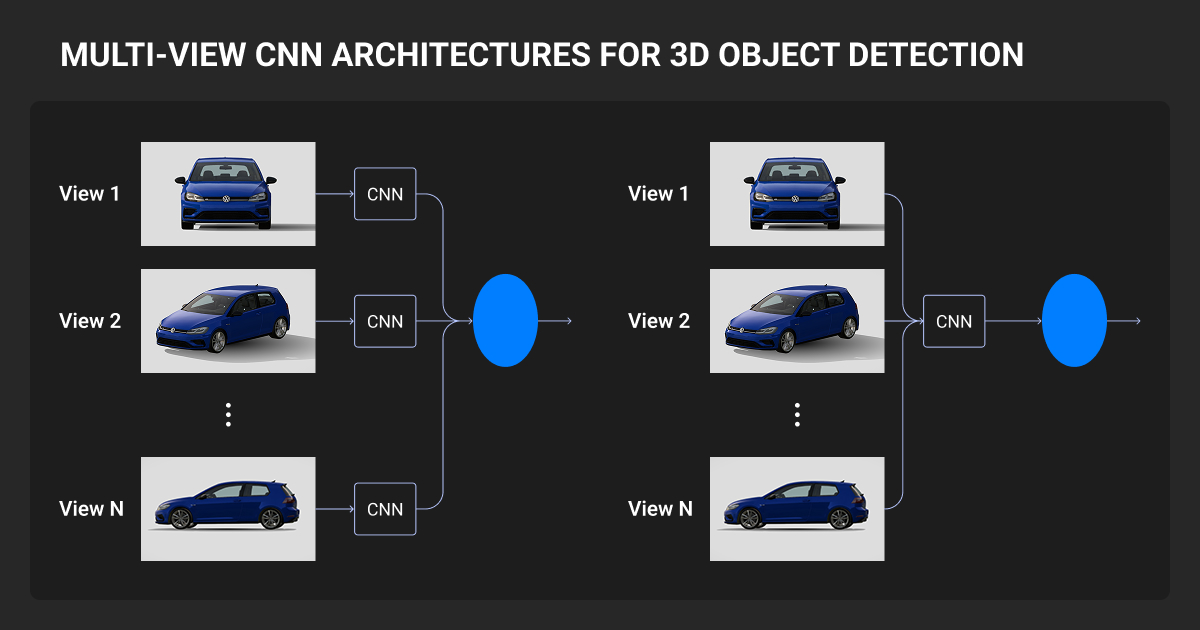

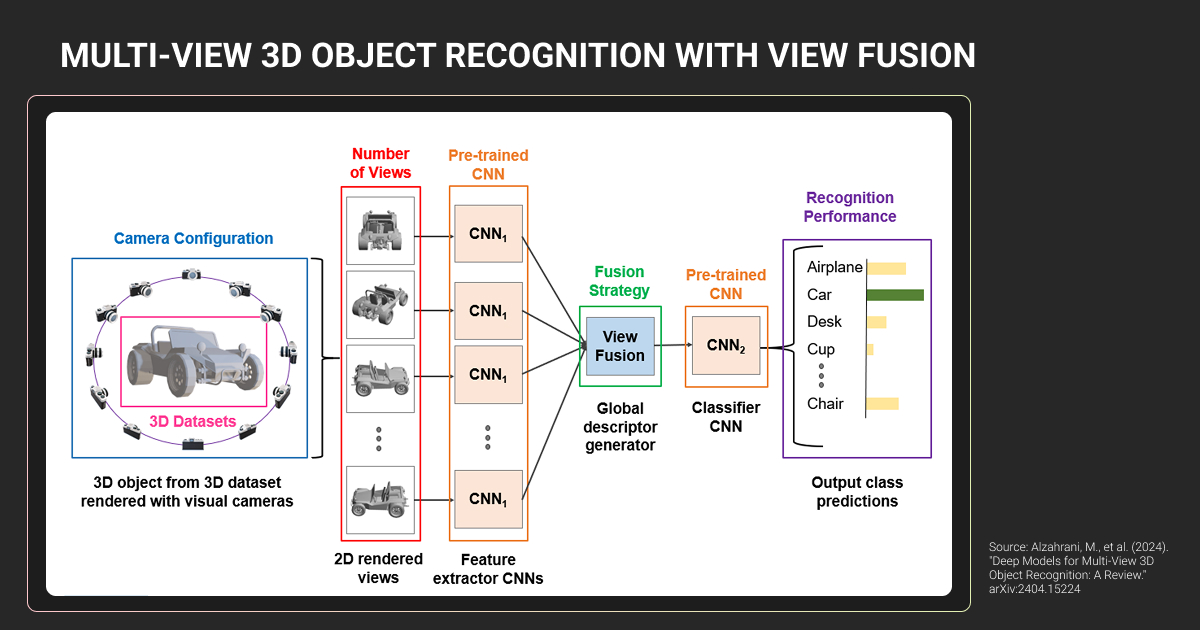

- Multi-view images infer depth from multiple camera angles. Attractive when hardware cost or form factor rules out LiDAR.

Choice depends on constraints, not ideology.

Why 3D point clouds are hard to work with

Point clouds don’t behave like images. Millions of XYZ coordinates scattered through space with no natural order, fixed resolution, or guarantee that nearby points belong to the same object.

Challenges:

- Sparsity: Distant objects have far fewer points

- Irregularity: Points are unordered; standard convolutions don’t apply

- Occlusion: Only surfaces facing the sensor are visible

- Noise: Rain, fog, dust, reflective surfaces create spurious/missing points

- Coordinate complexity: Data starts in sensor space, must align to world frame

This is why point-cloud-specific architectures treat data as sets rather than grids. It’s also why 3D object detection and labeling is slower and more ambiguous than 2D. You’re making geometric judgments with incomplete information.

The processing pipeline reflects this complexity: raw sensor data → preprocessing (noise removal, ground filtering, coordinate alignment) → feature extraction → proposal generation → classification and localization → post-processing and tracking.

Each step narrows uncertainty rather than eliminating it.

The greatest hurdle to overcome is that the current systems for 3D object input provide an inconsistent level of quality due to a variety of reasons, such as sensor type, resolution levels, and significant variation in data annotation quality. As a result, your model is not only learning how to identify objects but also how to adapt in an unstructured and chaotic environment.

Best sensors for 3D object detection in robotics

| Sensor type | What it’s good at | Main limitations | Typical use cases |

| LiDAR | Accurate distance and geometry | High cost, weather sensitivity | Autonomous driving, outdoor robotics |

| Stereo cameras | Depth from multiple views | Struggles with low texture and lighting | AV, mobile robotics |

| RGB-D cameras | Dense depth at short range | Limited range, indoor bias | Manipulation, indoor robotics |

| Radar | Long range, robust in bad weather | Low spatial resolution | Speed and object presence cues |

| Sensor fusion | Balances weaknesses across sensors | Calibration and system complexity | Most production AV systems |

Most production systems use sensor fusion. No single sensor is reliable everywhere, but failure modes are complementary.

Common 3D object detection model architectures

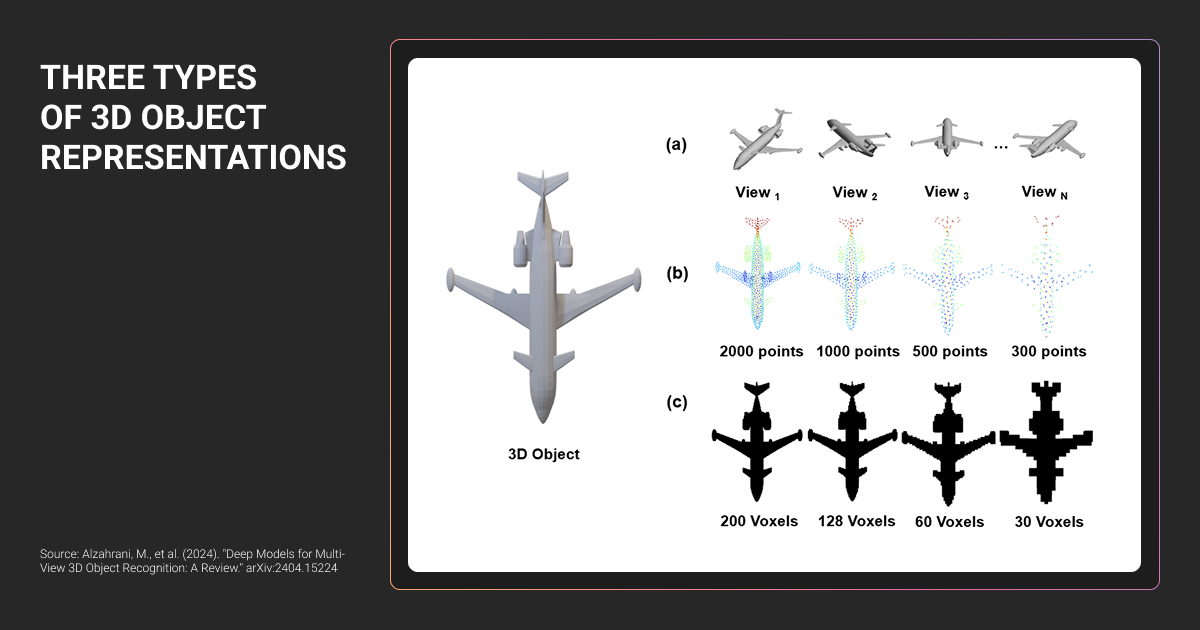

Most teams working with 3D object recognition point clouds end up in one of three machine learning algorithm approaches: point-based models, voxel-based models, or bird's-eye-view projections. Each trades speed, accuracy, and memory differently.

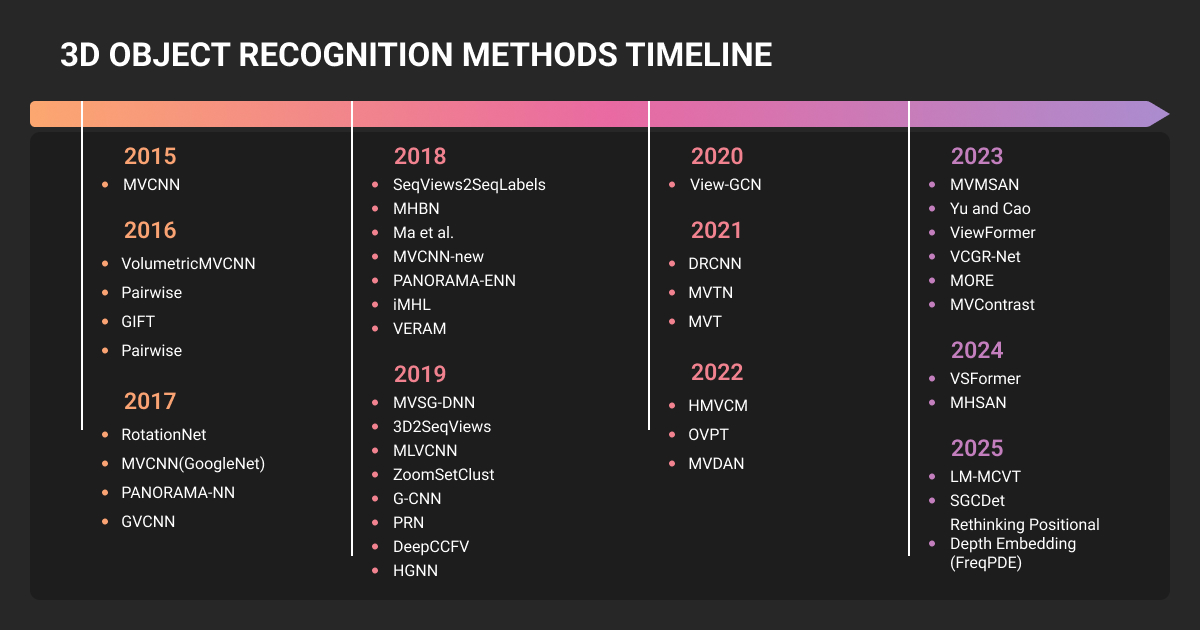

For teams evaluating specific architectures, this curated list of 3D object detection research provides a comprehensive overview.

Why data quality matters more than model choice

A simpler model trained on 50,000 cleanly annotated frames often outperforms advanced 3D object detection models trained on twice the data with inconsistent cuboid placement, unclear occlusion rules, or drifting orientation labels.

Recent foundation model approaches demonstrate this by prioritizing geometric consistency across diverse camera configurations over per-frame precision, achieving zero-shot transfer through stable 2D-to-3D knowledge mapping.

Architecture choices shape ceilings. Data quality determines whether you ever reach them.

3D Object Detection for Autonomous Driving

What autonomous vehicles need to detect

Vehicles need to detect cars, pedestrians, cyclists, lanes, curbs, and traffic signs — requirements that drive data labeling for autonomous vehicles strategies.

The difficulty is edge cases:

- Pedestrian partially hidden behind a parked van

- Vehicle stopped unexpectedly in moving traffic

- Cyclist far ahead, represented by sparse points

Missing an object can be catastrophic. False positives cause sudden braking and erode trust. Distance, orientation, and relative motion are the signals downstream systems use to decide whether to brake, slow, or continue.

Sensor configurations

Production AVs combine sensors for redundancy:

- LiDAR 3D object detection provides accurate geometry and distance

- Cameras add semantic detail (colors, signals, visual cues)

- Radar handles long-range detection in poor weather

Each sensor fails differently. When one degrades, another provides a signal.

Vision-only systems exist but operate with tighter margins. Depth is inferred, not measured. Glare, low light, or snow increase uncertainty, which matters in safety-critical contexts.

Dataset quality as a safety requirement

At AV scale, machine learning datasets quality becomes a safety issue.

Models need long-tail scenarios, geographic diversity, weather variation, and consistent annotation across hundreds of thousands of frames. Autonomous vehicle data collection at scale requires structured processes to ensure this coverage.

Common failure: model trained on sunny California data degrades sharply in Boston winter. Snow gets treated inconsistently (sometimes as noise, sometimes as occlusion) and the model has no stable reference.

The limitation is that the system never learned a coherent version of the world it’s being deployed into.

3D Object Detection in Robotics, AR, and Industrial Systems

- Robotics and warehouse automation: Bin picking, manipulation, navigation in clutter. Pose, orientation, and dimensions determine grasp safety and collision-free paths.

- AR and VR: Anchor virtual objects in real space. Geometry and occlusion handling make virtual content appear stable and correctly layered behind real objects.

- Industrial inspection: Shape and volume measurement. Dimensional checks, surface defects, tolerance verification can't be inferred from 2D alone.

- Retail analytics: Shelf monitoring, inventory tracking. Product dimensions and placement improve stock level reasoning and shelf compliance detection.

3D Object Tracking: Extending Detection Across Time

Single-frame detection shows what exists. Tracking shows what happens next. A pedestrian detected once might be standing still. Tracked across frames, you see steady forward motion, orientation shift, movement toward the roadway. The pattern lets downstream systems predict intent and adjust accordingly.

Tracking failures usually trace to annotation inconsistencies.

A car occluded in frame 10 reappears in frame 15 with a different ID because annotators handled the gap differently. Or boxes on the same stationary object shift 20cm between frames because orientation rules weren’t standardized.

The model can’t learn stable motion from unstable labels. What looks like a tracking algorithm problem is actually an annotation problem unfolding over time.

Training Data Challenges in 3D Object Detection

3D annotation is reconstructing a scene from incomplete evidence. Annotators fit 3D cuboids to point clouds or depth maps, define orientation angles, mark occlusion states, and assign attributes like vehicle type or pedestrian pose.

LiDAR annotation presents unique challenges: sparse points, sensor noise, and incomplete surface visibility require specialized workflows.

A single 3D cuboid takes 5-10× longer than a 2D bounding box. This directly affects data annotation pricing and timelines at scale because annotators are estimating where something exists in space.

Common 3d object detection and labeling errors

Small inconsistencies propagate into large failures:

- Bounding box misalignment: Model learns incorrect dimensions, struggles with distance estimation

- Inconsistent orientation angles: Vehicle heading becomes unreliable, breaks motion prediction

- Missing occluded objects: Model never learns partial views, fails in dense scenes

- Inconsistent 3D object recognition point cloud boundaries: Model becomes uncertain where objects start and end

At production scale, when Nodar needed polygon annotations for depth-mapping across ~60,000 objects, the difficulty was maintaining consistency while handling sensor-specific edge cases. Edge cases were logged, guidelines tightened through pilot feedback, and the team scaled to 20 annotators without rework cycles.

Our partnership results with Nodar: stable training signal that shrank validation cycles and held deployment deadlines.

One of the most difficult aspects of creating these kinds of 3D Object Recognition Models is acquiring accurate 3D labels. 3D labels are very expensive to obtain and most 3D Object Recognition Models will eventually have trouble recognizing very rare poses, or heavily occluded objects or Domain Shift objects.

Why guidelines and QA matter more in 3D

Edge cases are the norm: Is a person on a bicycle one object or two? How do you annotate a car with the trunk open? When is a pedestrian "occluded" vs. "partially visible"?

Without explicit rules, annotators make reasonable but inconsistent choices. That inconsistency is hard to spot and hard for models to recover from.

3D data annotation services require stricter guidelines and multi-pass QA. At Label Your Data, this means layered validation, inter-annotator agreement checks, and structured client review cycles to surface ambiguity before it becomes a training signal.

Scaling for production

Robust 3D perception needs 100,000+ annotated frames. At that scale, teams need a data annotation platform with point cloud visualization, multi-sensor alignment, and tracking-aware interfaces. Annotators need to understand 3D space, object physics, and sensor behavior—not just labeling rules.

Long-term partnerships with a data annotation company often form here. Ouster’s LiDAR annotation started with two Label Your Data annotators in 2020, scaled to ten as their machine learning pipeline matured. Required handling static and dynamic sensor data across interior and exterior environments where rules shift and edge cases proliferate.

A dedicated project supervisor maintained guidelines, trained new members, and kept turnover under 10%. Four years in, our annotations still feed performance regression analysis: 20% product performance increase, 0.95 weighted F1 score.

Same team for four years meant consistent 3D annotation quality — new teams reset and repeat the same mistakes.

About Label Your Data

If you choose to delegate 3D annotation, run a free data pilot with Label Your Data. Our outsourcing strategy has helped many companies scale their ML projects. Here’s why:

Check our performance based on a free trial

Pay per labeled object or per annotation hour

Working with every annotation tool, even your custom tools

Work with a data-certified vendor: PCI DSS Level 1, ISO:2700, GDPR, CCPA

FAQ

How much 3D data is needed to reach production-level performance?

Most production AV systems train on 100,000+ frames, but distribution matters more than volume. A model trained on 50,000 frames covering edge cases, weather variation, and geographic diversity will outperform one trained on 200,000 sunny highway frames. Coverage beats scale.

How should 3D object detection be evaluated beyond mAP?

Mean average precision (mAP) measures per-frame accuracy. Production cares about temporal consistency: does a tracked car maintain a coherent trajectory across 50 frames, or does its predicted position jump around?

MOTA (multi-object tracking accuracy), average displacement error, and false positive rate under occlusion tell you whether the system works when it matters.

When does sensor fusion outperform LiDAR-only or vision-only setups?

When failure modes don’t overlap. LiDAR degrades in rain. Cameras fail at night. Fusing them covers blind spots. Vision-only works in controlled conditions but breaks easily. LiDAR-only gives geometry but misses semantic cues (traffic light colors, lane markings). Safety-critical systems fuse because redundancy matters more than cost.

How do annotation guidelines impact tracking and prediction quality?

Inconsistent rules break tracking before the model trains. If one annotator keeps full boxes during occlusion and another shrinks to visible points, the tracker learns noise instead of motion. Clear rules for object identity and orientation directly determine whether the model can predict velocity and intent.

What are the most common failure modes when deploying 3D detection to new environments?

Domain shift breaks models fast. New geography means unfamiliar road layouts, signage, driving patterns. The weather the model never saw (snow, fog, heavy rain) degrades sensors in ways it can’t handle. Annotation inconsistencies that didn’t matter in testing suddenly break everything when edge cases become common. Most deployment failures trace to dataset gaps, not architecture.

Written by

Karyna is the CEO of Label Your Data, a company specializing in data labeling solutions for machine learning projects. With a strong background in machine learning, she frequently collaborates with editors to share her expertise through articles, whitepapers, and presentations.